SAN FRANCISCO — The salt air was my first breath. The murmuring tide of the Oakland estuary, my first lullaby. I entered the world not with a cry, but with the deep, rolling whisper of the Bay itself – a sound of constant, graceful collision.

My genesis was pure East Bay: a military hospital bed at the now-ghostly Oak Knoll Naval Hospital, my mother's Laney College textbooks stacked nearby, the scent of yeast from the old bakeries mingling with the diesel of port trucks and the polished leather of my father's military boots.

My family tree was rooted in resistance, in Black Panther boldness that spoke of a people, a place, fiercely devoted to its own.

I came into a world where resistance was breathing, where the Bay Area wasn't just a place but a posture—a way of standing against the wind and demanding it move.

This was my inheritance.

Not money, not land, but atmosphere. Culture.

The Bay.

The way the summer fog, a great gray blanket, would smother the Golden Gate. How the hills of San Francisco didn't just sit there; they rolled, majestic and muscle-bound, across the horizon.

CLIFFORD OTO/THE STOCKTON RECORD / USA TODAY NETWORK

The Golden Gate Bridge as seen from Fort Point in San Francisco on Aug. 9, 2018.

I fell in love with football the way you fall in love with anything that matters: suddenly, completely, without consent.

To me, the San Francisco 49ers aren't just a team; they are a birthright.

They were the dynasty that rose as I learned to walk, that dominated as I learned to read, that became mythology as I learned to believe in things larger than myself.

My childhood was soundtracked by a different kind of collision. The crack of shoulder pads, the roar of a kingdom called Candlestick ParkPark.

My first football memories were not of plays, but of mythology in the making. I was baptized into the faith just as the dynasty was born.

I learned my alphabet not with apples and balls, but with names that rang like cathedral bells: Montana. Rice. Lott. Young. Walsh.

These weren't just players. They were knights. And their king was a young, fiery Ohioan named Eddie J DeBartolo, Jr.

For years, the legend of that time felt like a family heirloom, polished by nostalgia.

I didn't know then what I know now—that what I was witnessing was the construction of something that would never happen again.

DeBartolo didn't just own a football team; he crafted a kingdom. And in the center of it all, standing beside him like a knight at the round table, was Carmen Policy.

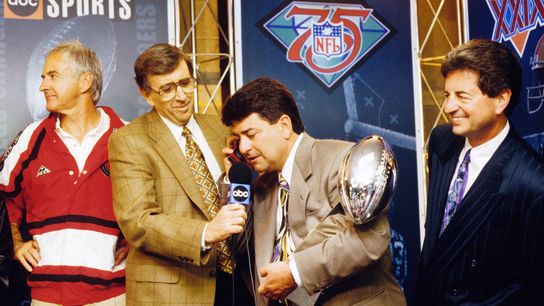

"I just fell in love with the whole city," Policy told Arash Markazi in an exclusive interview on the AMC four-part docuseries "Rise of the 49ers," where he pulled back the curtain on the creation myth. "I just couldn't wait to go back."

I-Ting Lee

Policy, the architect beside the king, made it all visceral, intimate, real. As Debartolo's personal attorney from Youngstown, Ohio—a place as far and culturally different from San Francisco as Taipei is to Texas—Policy accompanied Eddie D when he purchased the 49ers in 1977, and together they constructed something that Bill Walsh would later call "Camelot."

Policy spoke of DeBartolo, not as a distant owner, but as a force of nature.

"His passion can be very, very animated. And at times, very intense," Policy said.

He described the mission with elegant simplicity: Eddie would give the players everything they needed to succeed, and in return, he demanded their all.

"He carried a family attitude," Policy explained. "His approach was, I'm going to give you what you need to succeed. I want loyalty and commitment from you in the process, and commitment means you're gonna play your heart out."

That was the covenant.

That was the magic.

Eddie didn't just pay players—he loved them. He flew them first class. He put them in the finest hotels.

He remembered their birthdays, their children's names, their mothers' ailments.

He treated football players like family, and in return, they played like warriors.

Bob Deutsch-Imagn Images

San Francisco 49ers owner Eddie DeBartolo Jr. talks with running back Tom Rathman (44) on the sidelines against the Denver Broncos during Super Bowl XXIV at the Superdome. The 49ers defeated the Broncos 55-10.

"He felt they were being honest to themselves… and he owed them something back in return," Policy said.

Policy's description of their origin story cements the era's magic.

In a restaurant bar in Youngstown in 1977, a frenetic DeBartolo waves him over.

"He looks at me, and he says, 'I just bought a football team," Policy said.

Policy, baffled, assumes it's the Cleveland Browns.

"Ed says, 'So I didn't buy the Cleveland Browns, I bought the San Francisco 49ers.'"

To two Ohio boys, San Francisco was Singapore. It was Mars.

It was, as Policy recalled with a chuckle, "a little, shall we say, out there."

And why buy them? "Because it's for sale," Policy recounts.

That was the first spark. From that whimsical, almost absurd purchase, a Camelot was built.

Policy and DeBartolo, the legal mind and the boundless heart, became stewards of something that transcended sport.

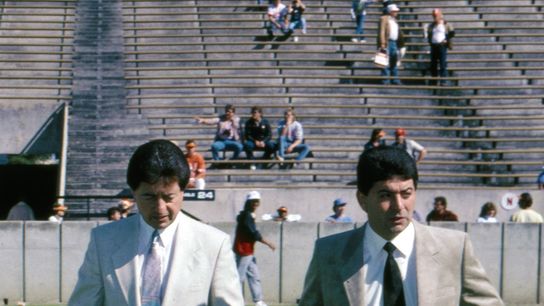

Imagn Images

San Francisco 49ers owner Eddie DeBartolo Jr. (right) and general manager Carmen Policy (left) on the filed prior to a game against the Tampa Bay Buccaneers at Tampa Stadium

They didn't just build a team; they curated a culture of fierce loyalty and family.

Players weren't assets. They were brothers.

Bill Walsh was the genius. Joe Montana was the general. But the dynasty was built on more than two men.

It was built on Ronnie Lott's violence, Jerry Rice's precision, Steve Young's desperation, Charles Haley's fury and Roger Craig's versatility.

Roger Craig.

The name still makes my chest tight.

The running back who could do everything—run between the tackles, catch passes out of the backfield, block like a lineman, score from anywhere.

Tony Tomsic-Imagn Images

Roger Craig celebrates his third quarter touchdown during Super Bowl XIX against the Miami Dolphins. The 49ers defeated the Dolphins 38-16. Craig set a Super Bowl record of three touchdowns in the game.

He was the first player in NFL history to have 1,000 yards rushing and 1,000 yards receiving in the same season. He won three Super Bowls. He made the Pro Bowl four times.

He was Marshall Faulk, LaDainian Tomlinson and Christian McCaffrey before any of them donned a helmet.

And he waited. And waited. And waited.

For years, Craig watched lesser players enter the Hall of Fame while he remained outside, his contributions somehow forgotten, his greatness somehow overlooked.

It was a crime against football, a sin against history, a reminder that the voters in Canton sometimes forget what greatness looks like.

But finally, this week, as San Francisco hosts the Super Bowl, the call came.

And when it did, two of his teammates, his brothers—Lott and Haley—greeted him, welcoming him home.

When Roger Craig opened the door, everything changed. See his Hall of Fame moment in “Hall of Fame Knocks: Class of 2026,” on NFL Network, Saturday, Feb. 7, at 10 p.m. EST. Class of 2026 presented by @VisualEdgeIT. @49ers @NFL @nflnetwork pic.twitter.com/f18ZmyvJZq

— Pro Football Hall of Fame (@ProFootballHOF) February 6, 2026

"Roger was the heart of our offense," Lott said. "He did things no one had done before. He deserved this."

Haley, the fierce pass rusher who battled his own demons, nodded in agreement.

"We built something special," Haley said. "Roger was a huge part of that."

That truth echoed decades later, punctuated not by a trophy, but by a long-overdue coronation.

Their presence was a testament to the bond Policy described, a bond that outlasted careers, that defied time. It was the final, living proof of the family Eddie D. built.

From 1981 to 1995, the 49ers won five Super Bowls.

They revolutionized the sport. They turned the West Coast offense into a religion and the NFL into a spectacle.

They became cultural unifiers in a region that was transforming—Silicon Valley rising, the earthquake of '89 shaking, the LGBT movement marching, the wine country blooming.

I witnessed portions of it; the others, my father ensured I watched VHS recordings to understand the significance of the dynasty I grew up under.

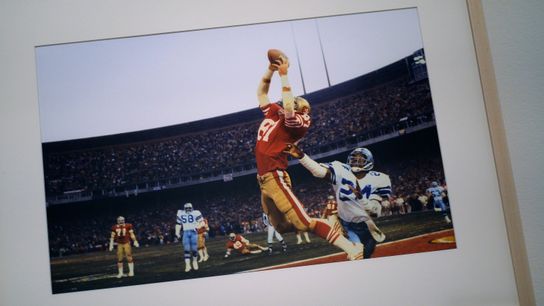

I remember watching my father playing, "The Catch"—Dwight Clark's fingers grazing the sky against Dallas in '82, the play that started it all —until the recorder started to singe the tape.

DOUG HOKE/THE OKLAHOMAN / USA TODAY NETWORK

The 1982 image \"The Catch, Dwight Clark, San Francisco, California\" is featured in \"The Perfect Shot: Walter Iooss Jr. and the Art of Sports Photography\" Thursday, March 3, 2022. The retrospective, which includes 85 photographs spanning 50 years of Iooss' career, is on exhibit at the Oklahoma City Museum of Art through Sept. 4.

I remember Super Bowl XIX, when Montana outdueled Dan Marino, and the 49ers proved they were more than a one-year wonder.

I remember the devastation of '87, when they lost to Minnesota in the divisional round, and the redemption of '88, when Walsh won his third title and walked away.

I remember the transitions—Walsh to Seifert and Joe to Steve, the Montana loyalists screaming betrayal, the Young believers preaching patience.

I remember the two NFC Championship losses to Dallas, the heartbreak of watching Jimmy Johnson's Cowboys bully the team I loved.

Policy remembers Eddie's promise after that second loss: "Can't have this happen again. I won't let it happen again."

And I remember the last hurrah—1994, the free-agent spending spree, Deion Sanders for one glorious season, Young finally escaping Joe's shadow with six touchdown passes against San Diego in Super Bowl XXIX.

For over two scores, I have remained faithful; faithful I will forever be.

Walsh called it Camelot; he named it himself.

King Arthur's legendary castle typified an idyllic kingdom of chivalry and happiness, but it also symbolizes any utopian place or time, and, like all Camelots, its sunset was ordained. By definition, Camelot cannot last.

The league, as Policy explained with poignant irony, literally created the salary cap to tear down what the 49ers had built.

"Everything they did was designed to tear down the 49ers," Policy said.

The magic couldn't last. It was too pure, too potent. The NFL made sure of that.

DeBartolo was forced out by scandal.

The dynasty crumbled. The Dark Ages arrived.

Ever since, the franchise has fallen short of reclaiming its once-golden standard of excellence and dominance.

"The NFL isn't built that way any longer," the docuseries admits. "Then-owner Eddie DeBartolo treated the 49ers as if they were the current Dodgers, outspending everyone else to the point where salary caps were instituted to level the playing field."

The younger generation of 49ers fans knows only disappointment—three lost Super Bowls, two to Kansas City, one to Baltimore.

They know Kyle Shanahan's brilliance and his heartbreaks.

They know McCaffrey's injuries and the Santa Clara substation jokes.

But I know Camelot.

I know what it felt like for my team to be invincible, to believe that the 49ers would always win, that Eddie D would always take care of his players, that Bill Walsh's genius would never fade.

Covering the Super Bowl in the Bay Area allows me to again breathe that salt air, still watch the fog roll in and envelop the bridge like a blessing.

Kirby Lee-Imagn Images

The Sporting Tribune's Eric Lambkins II at Super Bowl LX press conference at the San Jose Convention Center.

This week, I've passed by the ghost of Candlestick Park, headed towards Levi's Stadium, still believing that someday—maybe someday—Camelot will be rebuilt.

But I know it won't.

I know that what Policy and DeBartolo built was a miracle of time and place and personality, a confluence of genius and generosity that the modern NFL, with its salary caps and its analytics, cannot replicate.

Craig is now in the Hall of Fame.

Lott is there. Haley is there. Montana, Rice, Sanders, Young—they're all there, bronze busts watching in eternal silence.

Laine Farber

And when I visit Canton, when I walk through those halls, I don't just see football players. I see my childhood. I see my connection with my father. I see the origins of my love of the game of football.

I see the Bay Area in its golden age.

I see a family of Black Panthers and football fans, of revolutionaries and champions, of people who understood that greatness is built on love as much as talent.

Sports have an uncanny way of unifying people across religions, political affiliations, socio-economic and immigration status, identity and expression, and the confluence of other arbitrary wedge issues that divide us.

The 49ers became a cultural unifier.

And they did. For me, for my family, for everyone who ever smelled that salt air and believed in something larger than themselves.

The Bay Area fog still rolls in. The waves still crash. The Golden Gate Bridge still stands, majestic and eternal, with the clear, blue California sky still serving as a backdrop.

And somewhere, in the halls of Canton, Roger Craig's bust will smile—finally home, finally recognized, finally eternal.

Camelot lives.

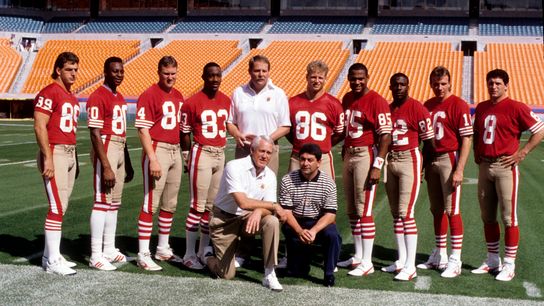

Imagn Images

San Francisco 49ers head coach Bill Walsh (bottom left) and Eddie DeBartolo Jr. (bottom right) pose with quarter backs and receivers including with Steve Young (8), Joe Montana (16), John Taylor (82), Jerry Rice (80), and assistant coach Mike Holmgren (center)during Super Bowl XXIII media day at Joe Robbie Stadium.

Not in the standings, not in the salary cap era, not in the modern NFL's cold calculus.

But in memory. In the stories we tell. In the love we carry for a team, a time, a place that will never come again.

So now I hold those memories close. I've tried to pass on the gravity to my sons.

They are as much a part of my Bay Area as the salt on my lips, the Panther history in my blood, the fog on the bridge, the nighttime majesty, as the light of the city flickers over the waters.

The dynasty wasn't just football. It was the spirit of this place – innovative, resilient, beautiful, brutal – captured in a game.

It was DeBartolo's passionate promise, Walsh's genius, Policy's steady hand.

It was Ronnie's hits, Jerry's grace, Joe's cool.

It was Craig, finally taking his rightful place, surrounded by his brothers.

It was a fleeting, perfect kingdom by the Bay.

And I was there.

I was born into the Bay Area's majesty. I grew up in the 49ers' dynasty.

And I will die believing that football, at its best, is not just a game. It's a family. It's a revolution.

It's Camelot, and Camelot, forever, is golden.