WESTLAKE VILLAGE, Calif. —Well this is awkward. Should I come back later?

I have only just walked into the Proactive Sports Performance Lab and already Don MacLean is administering a verbal lashing to a large man in droopy black Adidas shorts. The man is seven feet tall and wearing basketball shoes large enough to comfortably house a family of husky, Norwegian offensive linemen. I’m six-foot-three and even I must crane my neck all the way back to my hamstrings to look basketball giraffeman in the eye.

“You’ve got him on you,” MacLean barks, “the lightest guy in the workout, and you didn’t even act like you wanted the fucking ball, man. You’ve got to show him that you want the ball. Spread out, get big, and dunk on his fucking head.”

[Blink. Blink, blink.]

This is MacLean’s job now, and he is all in. With his UCLA and Clippers broadcasting gigs on hiatus, the PAC-12's all-time scoring leader is continuing his annual coaching boot camp for draft-eligible hoopers. The calculus here is actually quite simple: Weaknesses and wealth cannot coexist in the world’s best basketball league and MacLean's purpose is to coach potentially costly weaknesses and flaws out of these men while there’s still time. You get one shot at this, he tells them. You don’t get to come back to the draft again next year if it doesn’t work out this time. Direct. Confrontational. True.

There's a tinge of Detroit Lions coach Dan Campbell in his delivery—a do-or-die unwillingness to consider failure or poor effort. Whatever it is, it's working. In recent years MacLean's aggressive, no-nonsense manner has aided in fortifying the draft positions of several current NBA players, including the Clippers' Paul George, Minnesota's Karl-Anthony Towns, Cleveland's Donovan Mitchell, and former Bruin and fellow Ventura County native Jaime Jaquez Jr. (Miami). Quite a track record, so his words land like a pile-driver off the top rope.

MacLean knows what it takes to achieve success in the league, and he sees it as his duty to make sure players enter the professional ranks with eyes wide open. He frequently reminds them that pro-level skills like initiating contact with defenders without fouling or forwards switching on defense to pick up quicker guards are imperative if they wish to succeed. He would know.

There's a running joke among the assembled players working out with MacLean, and it has to do with apparel.

"If he's wearing tights under his shorts, that means it's going to be a tough workout," says one, who is projected to be a mid-first round pick.

Today MacLean is wearing black athletic tights under his shorts, and the eff bombs are flying around like embers from a campfire.

THE REAL BROS OF SIMI VALLEY

With the possible exceptions of actress Shailene Woodley and retired Angels pitcher Jered Weaver, Don MacLean is Simi Valley High School’s most well-known alumnus. He was a local celebrity by the time he was in middle school and our simultaneous arrival at the same high school offered me the chance to watch MacLean evolve from a tall-for-his-age Simi kid who could dunk to a bona fide national phenom. He led Simi High to a CIF championship near the end of our senior year (1988) and was recruited by virtually every competitive collegiate team in the country.

He scored more than 2,600 points in four years at UCLA and became the school's all-time scoring leader (for perspective, MacLean scored almost 300 points more than Lew Alcindor did as a Bruin, although he did so in four years to Kareem’s three). Beyond that, he is the PAC-12's career points champion—more than Kareem, Gary Payton, Reggie Miller and, by about 60 points, Sean Elliot.

MacLean was chosen nineteenth overall in the 1993 NBA Draft by Detroit and traded on draft night to the Washington Bullets (Shaquille O’Neal was the first pick that year). He was named the NBA’s Most Improved Player in 1994 when he scored on more than 50% of his shots. In all, MacLean played nine years of professional basketball, averaging almost 11 points and four rebounds per game while playing for the NBA teams in Washington, D.C., Denver, Philadelphia, New Jersey, Seattle, Houston, Phoenix, Miami and Toronto. He was traded eight times before the Toronto Raptors waived him on Oct. 29, 2001, thereby ending his playing career.

I went to high school with MacLean in the same way that I go to Laker games with LeBron James, which is to say we were both in the building at the same time. That's where any sort of "with" stops. MacLean and I resided at opposite poles of Simi High's popularity spectrum in 1988. He was six-foot-nine, scoring 32 points per game, and his ascension to big-time college ball and the NBA was merely a matter of time. Conversely, I was on the speech and debate team and occasionally forced to wear my orthodontic headgear to school. In our yearbook, MacLean was the student our class voted Most Likely to Succeed. I was voted Most Likely to Die Without Ever Kissing a Girl.

[Ed. Note: I kissed Jen Mathews in 1989 and she kissed me back. On purpose.]

The truth is I never actually spoke to MacLean until I did so in my capacity as a reporter. In my senior year at Simi High I got what amounted to an unpaid internship at our local newspaper, the now-defunct Simi Valley Enterprise. My beat, they said, was my own high school. Even as a classmate of MacLean's, I covered him for Simi's 120,000 residents. While he was evolving into the finest athlete Simi High has ever produced (hat tips to Weaver and his brother Jeff, Angels offensive coordinator Tim Laker, and former MLB pitcher, coach and punk rocker Scott Radinsky), I was learning how to be a sportswriter. We grew up together, but apart.

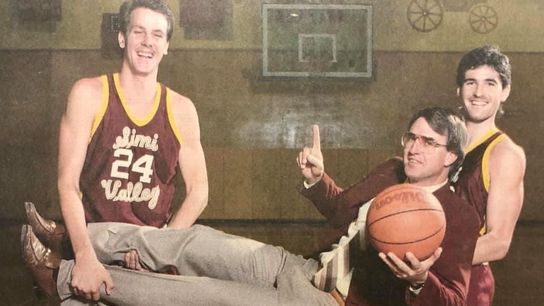

Left to right: MacLean, former Simi Valley High School head coach Bob Hawking, and the 1988 CIF Champions' second-leading scorer, Shawn Delaittre, who played collegiately at Eastern Washington.

Left to right: MacLean, former Simi Valley High School head coach Bob Hawking, and the 1988 CIF Champions' second-leading scorer, Shawn Delaittre, who played collegiately at Eastern Washington.Thirty-six years later, I find myself taking some solace that his hair is graying and ever-so-slightly receding just as rapidly and resoundingly as mine. But we are not the same. MacLean possesses something I do not, and for many years I believed that thing was arrogance. It's not. It's something far less sinister. As the hours pass and the eff-bombs flow, I start to identify that quality as zeal. He knows one way to build a basketball player, and he believes in that way because it worked for him. It's working for his three sons (his youngest, Trent, is a six-foot-nine small forward at Thousand Oaks High School going into his senior year and he is starting to field college offers). And he believes it will work for these players, too.

"If you set a tone for how you want things done, they get done that way," he says.

There is an understanding in this gym: you are here to work harder than you've ever worked before because the stakes are higher than they've ever been for these players. Life-altering money and opportunity on the line. No one's laughing or dogging it. I haven't seen a smile in three hours. On the wall behind one of the baskets in the Proactive Sports Performance Lab's basketball court, a question is posed in ten-foot-tall letters: "What are you capable of?"

I ask MacLean that question. Has he ever thought about full-time coaching?

"I always thought I'd be a pretty good coach," he says, "but my goal was always to arrange things so I don't have to move. I live here. I have roots here. I got to coach my sons here. I'm pleased with how things have worked out."